Verlon Herndon showed up at the put-in on the Salmon River wearing a hat with earflaps, a growth of dark stubble, and a faded vest with his name and phone number Magic Markered on the back. A haze of sleep deprivation clung to him like a scratchy cowl, although he was trying hard to shake it off with pulls from an oversized travel mug. It was as clear as the Idaho sky that the new was off Verlon, and off his driftboat, too.

I knew right away that I’d like him. But then, I tend to like men named Verlon, the same way I like women named Hazel or Gladys. When I found out that Verlon was born and raised in Oklahoma, it didn’t surprise me a bit.

I could tell from the grin on John McMahon’s face that he felt the same way. Verlon started us out ripping streamers, hoping to turn a big cutt or even a bull trout, and when that didn’t work he swapped them out for those ubiquitous Western hopper-and-dropper rigs. But instead of rigging the hoppers dry, Verlon rigged them “drowned,” dipping them from a water-filled mayonnaise jar where they’d soaked overnight. This recipe was new to me, as was his way of attaching the dropper with a split loop.

Verlon knew his business, but he didn’t make a big production out of it. He was watchful, economical in his movements, always thinking a few steps ahead. I was liking him more all the time.

We started picking up a few fish, with John accounting for most of the trout and me assuming my usual mantle of Whitefish Master. Verlon offered an occasional tip on mending line for a better drift and not overlooking good water near the boat, but unlike a lot of the guides John and I have fished with he was mostly content with how we presented our flies.

Coursing through the high desert, the Salmon commands a landscape so grandly austere it seems lifted from the Book of Exodus, only with the Israelites waving fly rods and the prophets pulling oars. Soon we settled into the easy familiarity of people who share similarly modest ambitions: a pleasant day on the water with enjoyable companions, enough tugs on the line to keep things interesting, and at least the possibility of something truly memorable. We told off-color jokes that were stale before Monica Lewinsky bought her first beret, and we volunteered just enough bits and pieces of our personal history to compose a rough sketch of the men we imagine ourselves to be.

After lunch, with John in another boat in our three-boat flotilla, Verlon and I found a slick dimpled with risers. Noticing a few motelike Baetis batting around, I announced that I was clipping the dropper and switching to a dry.

“I like the way you think,” Verlon said.

The risers turned out to be whitefish (surprise!), but when that’s what the river is offering, the gracious response is to accept it. There’s something about the sight of fish plucking flies off the surface that cuts through imagined prejudice, too.

Verlon dropped anchor parallel to the sweet spot, and for the next 45 minutes we whooped and hollered like schoolboys chasing girls around the playground. The whitefish were plentiful, willing, and good-sized; they pulled hard, and so what if they weren’t trout? It was fishing the way it used to be and now too rarely is, a throwback to that time when what mattered wasn’t the fish’s pedigree but whether it was putting a bend in your rod.

And, at the risk of giving myself too much credit, I think Verlon appreciated having a sport in his boat who was simply happy to see fish eat his fly, briefly feel their strength, and then let them go.

Finally Verlon called time, but we hadn’t floated far before I noticed a solitary rise in a curl of current tight against the rocks. I covered it and was rewarded with a fat 16-inch cutt. Verlon pulled out his digital camera and snapped a picture for posterity.

Later, in a deep channel where the water was so vividly aquamarine it seemed electrically charged, Verlon pointed out a lone salmon moving upstream, a relic of the vast runs that gave the river its name. Reading my mind, he quietly said, “Eight dams.”

We reached the take-out at dusk, the stern landscape softened by a cloak of purple shadow. Somewhere in the hills a coyote yipped. With the rods broken down, waders peeled off, and the driftboats secure on their trailers, I pressed a tip into Verlon’s hand and thanked him for a lovely day of fishing.

“My pleasure,” he said. “Hope we can do it again sometime.”

I hoped so, too, but you never know. And that’s why these partings can be bittersweet. Yes, you’re a paying client of someone providing a professional service, but that doesn’t mean you can’t connect.

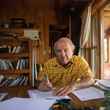

Verlon and I had exchanged e-mail addresses—speaking of making a connection—and by the time I got back from Idaho his photos were waiting on my computer. He’d also consolidated some of his fishing tips, which I promptly printed out and pinned to the corkboard above my desk. I appreciated his taking the time to do that, and as a token of gratitude I sent him a copy of one of my books.

A few days later, there was a message from Verlon in my in-box: “You never told me you were a writer!”

In the intimate confines of a driftboat, it’s best to think twice about full disclosure.

Comments