It wasn't so long ago that I was at the stage in life where a number of iconic figures in the art and entertainment world I'd grown up with had begun to pass out of this world. I am far from being a celebrity hound, but as I scanned the headlines each morning, it was sad and mildly shocking to see that an actor, singer, writer or other celebrity I'd long admired had been admitted to a hospital for the kinds of illnesses that portend the end, or that indeed the end had come. The blow I felt in such moments undoubtedly stems from the reminder that in fact we are, all of us, "in the queue."

More recently, feathered in among these noted artists, the mentor-friends of my boyhood have been departing. The deaths that have hit closest have been among the men with whom I had the honor of hunting and fishing, men I admired, studied closely and learned from. Lessons included the proper handling of firearms, where to look in a piece of water for trout, the pleasure of cold spring water from a tin cup, how to keep a canoe true to course, how to listen and see, but more importantly my association with these men provided vital guideposts along my own path toward — and into — adulthood.

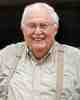

Among this pantheon, I doubt that there was anyone who had a greater influence on my young life than did Bill Kodrich. The winter I was 12, he taught me to tie flies, the very first of which was a lead-winged Coachman. I can still remember my clumsy fingers fumbling to tie in matched sections of Mallard wing. That spring at the small pond on his property, Bill let me borrow one of his fly rods as he showed me how to cast a fly line. That summer I used that very fly to quickly snatch (and release) sixty (60!) fat bluegills from a bed in just 30 minutes — a seminal feat I've never replicated but which clued me in to how incredibly effective fly-fishing could be. Later, Bill brought me into the fold of Trout Unlimited, an organization in which my wife and I are proud to be life members.

It was Ken Sink, then Pennsylvania TU Council president, who encouraged Bill to start a local chapter in Clarion, PA. Thus in 1975, with Bill elected as the first president, the Iron Furnace Chapter was born. Forty-nine years later the chapter is still going strong, fighting the good fight through educational outreach to local schools, restoring and protecting stream habitat, offering regular fly-tying lessons and advocating for the protection of stream-bred wild trout.

Bill's early leadership role in TU was but one point on a long arc that began in upstate New York where he was delivered at home on his parents' dairy farm. Along with neighborhood chums, Bill cut his teeth fishing for bullheads at a local pond. His initiation into outdoor pursuits thus began, it wasn't long before he found his way into trout fishing and grouse hunting. After graduating from Hartwick College in Oneonta, Bill took a position teaching high school science in Morris, New York. His desire to bring young people into the world of the great outdoors prompted him to start a rifle team at the school, and to anyone who has known Bill, it would be no surprise that his marksmen became the school's winningest sports team.

In 1967 Bill earned a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Pittsburgh. That same year, he joined the faculty at Clarion State College where he taught a variety of biology courses and was an advisor to graduate students pursuing advanced degrees in environmental science. "You could always tell which students were Bill's," his colleague Jack Williams recalled. "While other students were dressed for class, Bill's were dressed in field boots, carrying backpacks full of instruments and dragging hip boots down the halls of Pierce Science Center."

As with any person's life, historical context is important. Rachel Carson's pioneering call to environmental awareness, Silent Spring, was published in 1962. Bill would have been about 29, just beginning to narrow his focus from general science to environmental studies. Clarion County, Pennsylvania, at the time still one of the nation's leading producers of coal, provided a perfect venue for a young environmentalist setting out to make a difference. The landscape of my youth appeared almost as a war zone might — hills denuded of forest, barren gray flats where mountaintops had been stripped clean, lifeless acidic streams running orange with iron-oxide.

Back then, the Clarion River was nearly a biological desert. Effluent from paper mills, strip mines and towns along with farm runoff and deforestation — and before that, oil exploration — had taken a heavy toll. The river's acidic, silted, pollutant-laden water was barely capable of supporting a few stunted panfish and bullheads. Carp hung out below pipes carrying waste from communities. As beautiful as the river appeared in October when autumn leaves were reflected in its depths, any trout that might have migrated downstream from one the Clarion's relatively few clean tributaries was a goner. And "few" was the operative word. On Samuel A. King's stylized 1970 map, Cornplanter's Kingdom: A Field Map of the Allegheny National Forest, tributary upon tributary feeding the Clarion River is marked with a skull and crossbones. Paint Creek, Toby, Mill and countless others ran orange-red with the effects of strip-mining, and steady rain would send even the smattering of relatively clean flows up over their banks in a roily, muddy mess.

But change — big change — was on the horizon.

In 1970 the Clean Air Act was signed into law. Then came the real game changer: the 1972 Clean Water Act. As the river's myriad problems were addressed, Bill was in the thick of it — appointed to Pennsylvania's ad hoc Committee on Strip Mine Legislation. Later, Bill served as Pennsylvania TU's Environmental Committee Chair. As way led to way, he found himself elected as second vice president of the PA TU State Council, accompanied by an appointment as a delegate to TU National. He soon expanded his involvement on the national level by joining TU's Research and Projects Committee where he was responsible for vetting grant applications for the Embrace-a-Stream program.

In 1990, Bill was elected president of Pennsylvania TU. Two years later, he became the second person ever reelected as President of PA TU. (The other being Ken Sink.) It was at this time that, with Sink's help, Bill reached out to former President Jimmy Carter and convinced him to come to Pennsylvania to be part of a video promoting Pennsylvania Trout and to sign a series of trout prints created by Pennsylvania wildlife artist George LaVanish. President Carter's involvement was a boon to PA TU's fund raising and helped increase membership. During his tenure as Pennsylvania TU Council President, Bill also created the Trout and Salmon Management Committee to evaluate PA's coldwater fisheries. Even after Bill retired as president — after serving three terms — he continued to chair this committee.

Perhaps overlooked in all of this is that without Bill's leadership, Pennsylvania TU would likely have ceased to exist. Forces at TU National were looking at consolidating state chapters. Under the plan, PA TU would have been folded into the Southeast Region — a plan that puzzled some as PA's watersheds generally have little in common with those further south. Bill had the vision and skills to maintain the PA Council's independence, in the long run strengthening both Pennsylvania's conservation interests as well as those of TU National.

In addition to being a highly regarded faculty member and mentor to countless students and ushering many young people such as myself into the glorious world of trout, fly-fishing and hunting, Bill earned several awards, among them the National Trout Unlimited Distinguished Service Award, the Ralph Abele Conservation Heritage Award, and the PA Fish & Boat Commission's Award for Advancing Conservation, Fishing and Boating.

There were other awards, other committees, not to mention 25 years as a volunteer Deputy Waterways Conservation Officer. Having left Clarion when I graduated from high school in 1977, there's a good bit in the above that I did not know until, feeling that Bill deserved more than a few skinny paragraphs in the obituary sections of local papers, I picked up the phone and started calling old friends and mentors. Everything I was told in those conversations with people who had known Bill over the years rang true — from the way he started a championship rifle team as a high school teacher, to the hip-boots and backpacks approach he took to teaching college students, to the way he seemed — generally without much effort — to have a gift for keeping several plates simultaneously spinning while always moving forward.

In one important way, those conversations confirmed a kindred spirit I had always felt with my old mentor: As his friend Tim Fay recounted how Bill used to become so absorbed in watching damselflies and birds that he often missed strikes, I had to smile in appreciation of the well-heeled axiom that "it is not the fish we are after," my own life journey in fly fishing having led to studies of birds and flowers during years I spent living in a wilderness Aleutic village along the banks of a salmon river.

Bill's many accomplishments are to be admired and cherished. But when I think of him, what I remember is a man leaning over my shoulder, his easy voice in my ear coaching as I learned to wax thread and spin hair from a hare's ear; a tin cup held under a gushing spring and handed to me on my first ever deer hunt; an impromptu line-mending lesson on Pennsylvania's Spring Creek; or a tip offered casually in passing regarding the effectiveness of a nymph drifted passively under an indicator on a lake.

As important as those lessons were, it has been Bill's example that has had the greater impact. Were one to glance at my various tools, fly boxes, cookware and so forth, one might notice every drill bit accounted for and in its proper place, flies arranged in tidy rows, cookware stored thoughtfully, clean and cared for. "This is the way Bill would do it," I've said to my wife Barbra or thought to myself countless times. A fly rod wiped clean and returned to its proper place on wall pegs after a day's fishing, a ritual Barbara joins me in having joined the brotherhood of the angle, brings back fond memories of Clarion and of hunting and fishing with Bill. And, although Barbra never had the pleasure of meeting my old mentor, in this and other ways she too has come to know him. In fact, I find that as I pass by vegetable gardens here and there, compared with the impeccably well-ordered rows Bill attended to, all are somewhat wanting. And I never have a really good piece of pie that he doesn't come to mind. "We've got to fuel up if we're going to be spending the day..." hunting or fishing.

The testament of Bill's life — of the lives of all of these mentors from my youth — is that even a little attention cast to a young person can have an impact that lasts a lifetime. It is a legacy grander and more meaningful than the largest mansion, a pile of money to the sky, or fame in any measure.

Memorial donations may be made in the name of William R. Kodrich to the Clarion-Forest VNA, the Limestone Township Volunteer Fire Department, and the Alliance for Wetlands and Wildlife. There will be a memorial service honoring Bill's life on July 27, 2024 from 11:00 am, lunch served at noon, visiting to 3:00 PM at the Clarion Moose Club.

Comments