When on the water with friend and steelhead guide on Oregon's Deschutes River, Tom Larimer, any mention of the natural movement of the air in a current or particular direction is spelled, not spoken. It's considered bad luck to do otherwise. After all, wind is the fly caster's worst enemy. It butchers trajectories, displaces power, creates knots and impedes the angler's ability to translate load in the rod into a well delivered cast.

On a trout stream, being ill-equipped to deal with the wind can be a nuisance, but can usually be overcome gradually with patience and persistence. Even when steelheading, it can significantly change the game, but isn't usually a deal breaker. When in the salt, however, being unprepared to deal with the wind can mean missed shots and those missed shots can make for long, unproductive days.

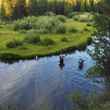

I've made no secret of my affirmed status as an average caster, noting it in rod and reviews and lamenting it in fishing tales. Yet, despite my pedestrian casting ability, I felt comfortable heading out to chase permit and bonefish on Mexico's Ascension Bay without proper time spent with rod in hand, fighting the wind and learning how to deal with it. Though I've spent my fair share of time fishing in the salt, and even in windy conditions, most of that time has been spent casting sinking or intermediate lines which allow an intermediate caster to get by in blustery conditions while lacking the skills to cope with those conditions with a more traditional, floating line.

As a result, I was forced to do my practicing on the water, under the tutelage of the excellent guides at Punta Allen's Palometa Club. These cats make their living on the often windswept flats of Ascension Bay and have developed the skills to handle the conditions. And while I've returned from Mexico a much better caster in the wind as a result of their instruction, it came at the expense of countless missed shots. The truth is, while dealing with the wind isn't easy, it can be done fairly readily with a bit of composure and proper technique. Even once armed with the proper technique, the composure part will likely only come with time and experience and — take it from me — you'd rather spend that time on the lawn than missing shots at never-to-be-seen-again 30 pound permit.

With that said, here are two tips for dealing with the W-I-N-D that will eventually find you, whether on the stream, in the surf or on the flats.

Stop Waving that Stick Around

Saltwater guides will find any number of ways to remind the trout fishermen that he is not on a trout stream. Most commonly, this will be in the oft-heard moniker, "don't trout set." Perhaps equally important is the notion that saltwater anglers, unlike freshwater anglers, don't enjoy the luxury of being able to false cast to their heart's content. Ttrout fishermen false cast profusely for any number of reasons: to get a better feel for the load on the rod, we learned to cast that way, the conditions afford us the time to do so, it's just plain fun, and so on.

When a cruising bonefish or permit is spotted, the time to present the fly to the fish is often mere seconds, making excessive false casting a recipe for a squandered opportunity. But wind is another prime reason to limit false casting. The longer your line is in the air, the more opportunity wind has to wreak havoc on your cast, blowing your line it as it chooses to, eliminating rod load and dissipating power.

All casters, but particularly novice casters, should try to eliminate false casting when faced with windy conditions. Instead, try loading the rod with a water haul on the backcast, shooting line forward on the first forward cast. This may require a roll cast or flip to reposition the line on the water's surface before backcasting, as well as a haul on the line, but the back-and-forward motion of the cast should be limited to one iteration. Attempting to do otherwise, especially in a crosswind, will dissipate load and result in a weaker and less-controlled forward cast.

Change Your Casting Plane

Freshwater fishermen typically have a go-to casting plane. For most, that plane is an overhead or slightly-tilted-from-overhead casting plane. For some anglers (like me) it is more of a sidearmed plane. But, whatever the case, it is usually only obstructions such as overhanging branches or stream side brush that will force us to deviate from our comfort zone.

The wind, however, can be viewed in largely the same way that overhanging branch. Just as that brush along the branch will cause you to think about your motion — elevating your casting plane — so should the wind.

Take a headwind, for example. Unlike in the case of that stream side brush, we're interested in modifying our casting plane not because of the obstructions that lie in the path of our backcast, but because of what our backcast means for our forward cast. Without wind, the angler's goal is to throw a forward cast on a plane parallel to the water that lays out and drops softly to the surface. With a strong headwind, however, this will result in a fly line that gets tossed back in your face. A caster unexperienced with dealing with wind will instinctively try to compensate with power, which will almost always be a futile effort. The solution is better technique, not elbow grease, and that better technique involves a change in casting plane. Instead of throwing your typical cast, toss an exaggeratedly high backcast, almost to the point where you feel like you're tossing your backcast straight up into the sky. In order to maintain load on the rod, you'll be required to deliver a forward cast with a decidedly downward trajectory. The result will be a cast that cuts through the wind and meets your target with power, rather than a flaccid cast that gets blown back in your face.

The same general principle can be applied to conditions where the wind is blowing heavily at your back, otherwise known as a tailing wind. Instead of trying to throw your backcast within your comfort zone — the aforementioned typical overhead plane — concentrate on throwing a low backcast, keeping your cast as removed as possible from the wind's influence. On the forward cast, aim high and let the wind assist in unrolling and laying out your cast.

Whatever the nature of the wind you find yourself faced with, the key is to be aware of the wind and how you should respond in adjusting your casting technique. Like much of your current casting ability, most of this will become instinctive after time spent practicing and feeling how the wind affects your ability to keep load on the rod and fly line. Whether that time is spent on the practice field or spent missing shots at permit is totally up to you.

These are certainly only two of dozens of helpful tips for casting in the wind. If you have your own tips for casting in windy conditions, be sure to share them in the comments below.

Comments

ginkthefly replied on Permalink

All very good tips, the casting plane one specifically.

Generally I think it is important to resist the urge to try to muscle everything. It seems like you have to, but you don't. The reality is that there is a limited amount you can do in the wind. BUT you can either do all of that limited amount, or struggle to do a fraction of it.

Your time is MUCH better spent learning the tricks/tools to deal with the wind rather than trying to power through it.

PoconoTrout replied on Permalink

The tip! The tip! It's all about the tip!

Carl McNeil replied on Permalink

There are 5 very specific things a caster can do to combat the wind - here they are https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ft5gL34fhQU

Anonymous replied on Permalink

In high-wind conditions, think about what your reasonable max casting distance is going to be (some combination of visibility, wind conditions, and whatever you think you can do) and make sure to have enough line outside of your rod tip to be able to accomplish it in either a single roll cast or one false cast. I will keep 10 ft of fly line + leader outside the tip which means I can basically lob it to a fish that is 25-35ft away with a half cast, or make a single false cast and get the 35-40ish distance which is as good as most of us will do when its blowing 20+

Pages