Like my mom did with me, I taught my kids to tie their shoelaces the wrong way. Bunny ears, bunny ears, jumped into the hole, popped out the other side, beautiful and bold. I didn’t teach them to wrap the loop in the wrong direction on purpose, of course. I did it because I didn’t know better. I taught them the way I was taught.

For years, my running shoes came untied when I ran, my wading boots came untied when I waded, and my ice skates came untied when I skated. My knots failed nearly every time I did the thing my footwear was made to do. Yet, somehow, in the face of failure after failure, it never occurred to me I might be doing something wrong.

Then, sometime around 2005, I watched a TED talk video by a guy named Terry Moore.

“I have reason to believe that many, if not most of you, are actually tying your shoes incorrectly,” Mr. Moore told the audience. “I know that seems ludicrous. And believe me, I lived the same sad life until about three years ago.”

Then he convinced the audience—and me—that many of us had been doing it the wrong way all our lives. It was a simple fix. All we needed to do was wrap the loop in the opposite direction before pushing it through the hole. At first, I didn’t believe it. Muscle memory took over nearly every time I was in a hurry. But I noticed that when I did it the new way—the right way—my shoes, boots, and skates didn’t come untied. When I fell back to the old way—the way I’d learned and hadn’t questioned for decades—they did.

More Like This

Something like that makes you think. What other things am I doing wrong that I think I’m doing right? That’s a tough question, because right and wrong can be relative things, especially these days. I was once told I loaded the dishwasher incorrectly despite the dishes coming out clean every time. Though I insisted my way worked, I’ve noticed the dishes are a little cleaner—and life much calmer—since I started doing it the right way. Perhaps there’s something to it. What else works well enough for me to believe I’m doing it right, even if I’m actually doing it wrong? Certainly nothing as important as fly casting. Right?

I learned to cast a fly rod in an era when asking a computer to show you lessons and tips was as useless as asking a phone to give you directions. Integrated circuits could only hold millions of transistors back then. They’d need hundreds of millions—or even billions—before that kind of witchcraft was possible. But today, your phone can tell you how to get where you’re going before you tell it where that is, and if you type fly casting lessons on your screen, you’ll have more hours of videos to watch than a muskie has teeth. And a few of those might even be helpful. The videos, not the teeth.

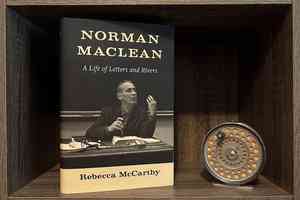

Now, when I say I learned to cast a fly rod, I mean I figured out how to attach the leader to the line, tie a fly to the leader, and wave the rod back and forth in a way that caused the fly to land somewhere around twenty feet in front of me, some of the time. I didn’t tie a tippet to the end of the leader. I just made it look that way by mastering the art of casting a wind knot a few feet above the fly. After a few outings, my leader had enough knots that a casual observer might think I was one of those lunatics who ties multi-segment leaders instead of buying tapered ones like a normal person. Even though I’d had a brief lesson from a skilled caster, the only thing I could tell someone about casting was it is an art that is performed on a four-count rhythm between ten and two o’clock. I had watched The Movie, after all.

I did all this in a remote town in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula where fly-casting instructors were as uncommon as black coffee at Starbucks. Plus, paying a person to teach you to fish seemed like the sort of thing rich folks did when they got bored from lighting Gurkha cigars with hundred-dollar bills. After a few years of functional—but inadequate—casts, I bought some books and DVDs, tied a piece of yarn to my leader, and practiced enough to discover that magical thing called a loop. Like Justice Stewart’s pornography, how I made a loop was hard to explain, but by golly, I knew one when I cast it.

Over time, I got good enough that Tim Schulz wind knots—or casting knots as they should be called—only appeared on the cover of milk cartons. Someone even wrote that I “cast like a dream.” I don’t tell you this to toot my horn, especially now that I realize my horn sounds like a duck with a mouth full of marshmallows. No, I tell you this to illustrate how unaware most of us are about what makes a fundamentally sound cast. Those of us, that is, who have never met John Juracek.

At this point, I should explain that I’ve seen how fireworks can illuminate the screen when a writer lights the fundamentally-sound-cast fuse.

“Give me a break. Any cast that gets the fly to the fish and fools it is a good cast. Anything more is overkill.”

I get it. I haven’t made that comment under my anonymous username Copernicast, but I’ve thought it. And like many of you, I’m good enough at catching fish that when things slow down for me, casting fundamentals is on my catalog of possible explanations somewhere between moon phases and what I had for breakfast. But for John Juracek and anglers of his ilk, casting fundamentals tops the list.

I met John at Todd Tanner’s Tao of Trout in October 2024, part of the recurring School of Trout program. I was there to observe the school and later write about the instructors, students, and curricula. To make my experience immersive, though, Todd insisted I participate as a student.

“Do you know I already cast like a dream?” I asked Todd with a wink.

“Oh, I have no doubt,” he said, “But John might find a flaw or two you could work on.”

“Okay, but I’ll hold back a bit so the other students don’t feel inferior.”

“Go ahead and give it your A game. I think they’ll handle it.”

From his first words, it was clear that John Juracek studied the mechanics of fly casting from the caster’s perspective, not the rod’s as so many do. Everyone agrees on what the rod should do to make an effective cast. Travel in a plane. Stay out of the line’s way. Load. Unload. That’s physics. John focuses, instead, on the caster and how they can make the rod do what it’s supposed to do in the most efficient and consistent way possible.

For many of us, though, the end justifies the means, provided the end means we catch enough fish to keep from getting bored. If we’re catching fish, our cast must be good enough. But that’s not how John sees it. For him, a fundamentally sound cast isn’t just a tool for a job. It’s an end in itself, not just the means to one.

“Do you want to cast more accurately?” John asked the class.

I want to cast more accurately.

“Do you want to cast better in the wind?”

I want to cast better in the wind.

“Most importantly, do you want to increase your enjoyment of the process?”

Yes. Yes. I want to increase my enjoyment!

Like a perfectly seated blood knot, that last question brought it all together. As much as I love fly fishing, there are still times, especially when it’s windy, when some problem with my cast sours my mood. So why not give John’s focus on the means a try? When in Rome, do as the Romans.

“Everyone, relax your casting arm by your side and let it hang naturally,” John told us.

Got it.

“Now, raise your forearm parallel to the ground, forming a ninety-degree angle at your elbow.”

Check.

“Pivot up from your shoulder and touch your forehead with your thumb.”

Okay.

“Now drop it back down to the original position.”

When will he show us his method for making a cast?

“Arm back up. Now, shift your hand from your forehead to above your shoulder. But don’t open your shoulder.”

This is getting goofy.

“Arm down. Arm Up. Down. Up. Do it several times, and notice how you pivot in your shoulder, not your elbow.”

Why are we doing this?

“Okay. That’s how you cast.”

No, it’s not. My arm should be away from my body and pivot at the elbow, not the shoulder. That’s how you make a loop.

“What’s your elbow doing, Tim?”

“The wrong thing?”

“Yes, pivot at your shoulder and move your elbow up and down. Cast from your shoulder, not your elbow.”

“This is what a mechanically sound fly-casting stroke looks like,” John told us while lifting and lowering his arm.

Uh oh.

Tiger Woods said rebuilding his golf swing involved unlearning the old muscle memory and relearning the new. That’s simple enough, but unfortunately, unlearning and relearning have to happen at the same time. When my mind said Ninety-degree bend at the elbow and pivot at the shoulder, my arm said Do it the way you used to. The result was something resembling a drunk octopus hailing a cab.

“What’s going on with your elbow?” every instructor asked me. I knew I needed to break down my cast to build it back up, but to do that, I had to stand on a lawn with ten other students and absorb the occasional This guy writes about fly fishing? whispers from the crowd. But a better cast would be worth it.

They say when you hit rock bottom, you’ll know it, and after a drift-boat-load of casting knots and tangled lines, I was there. There were two paths to get out of this hole. I could either go back to my old way of casting or fully commit to the new way. When the bet came to me, I pushed my chips to the center of the table and asked John and the other instructors to help me remember to forget and forget to remember.

“This is the stroke the best fly casters in the world use,” John said. “They use it because it’s suitable for any kind of fishing, anywhere at any time. Master it, and it will never get you in trouble.”

Back home, I’ve been practicing in my yard, seeing—and feeling—the progress. Wind and fatigue don’t bother me like they used to. I have more accuracy. My fly doesn’t float like a leaf spinning in the wind after my line lands. I don’t use a different stroke when I switch from a fast to slow rod. Just slow the same stroke down. In short, my casts don’t come untied like they used to.

Up here, in Cliché County, Michigan, we like to say leopards won’t change spots, old dogs can’t be taught, bent sticks won’t go straight, and yellow snow don’t taste great. Despite all that, we pride ourselves in being open-minded about most things. Well, except for the yellow snow. So, while waiting for the snow to melt, I’ve been thinking about other things I might improve. Turns out, I’ve been peeling bananas the wrong way.

Comments

Kerry replied on Permalink

I’m afraid to look. But I’ll bet there are videos on “How to wipe your butt - the right way!”

BobWhite replied on Permalink

Great article, Tim!

I wish John had taught me to cast from the get-go, before I taught myself... and learned all of my bad habits, that nonetheless work just well enough to make me believe that this old dog doesn't need any new tricks.

I look forward to seeing you at the Great Waters Fly Fishing Expo in March!

Henry Kanaemoto replied on Permalink

I was taught to cast and fly fish by Gary Borger. His son Jason Borger was the casting double for Brad Pitt in "the River Runs Through It." The method you describe is the "Foundation Cast" and is the basic cast used many instructors and is the basic cast used by world champions including Maxine McCormick, who won the women's division fly casting championship in 2016 at age 12.

Pages