The waterlogged, wrist-thick cedar branch probably came to rest on the gravel bar as the tide retreated. It’s a big tide on Alaska’s Prince of Wales Island — 15-foot fluctuations between high and low aren’t unheard of. But there it sat, this salt-soaked branch coated in sea slime and a few barnacles. It was heavy and sturdy. Just what I needed. I lifted the branch—about the size of a police baton—and brought it down swiftly on the head of the silver salmon I’d spent the last 20 minutes fighting, killing the fish instantly.

Dinner.

We’d been patrolling the estuary streams of the island for a few days by the time we finally “got into” the silvers. And even then, the catching was spotty. The hope, of course, was that we’d catch our limit every day and have enough to freeze and pack into 25-pound boxes as checked luggage for the trip home. We’d also been hoping to catch enough to feed the three of us over the course of a week on the island without having to dip into the stash that was to be flash-frozen and boxed up for the trip home.

The reality was quite a bit different. As we walked along the grassy banks of this particular salmon stream — one of the most remote we’d visited — my buddy Mark was the first to get a grab from a coho. It was a nice fish. Maybe five pounds and still pretty bright. Of course, it was hooked within sight of the salt, and its first inclination was to run downstream, back to the Pacific. It put up an appreciable battle, but Mark was quick to turn it, and the three of us did a little quiet celebrating. At the very least, we’d have something on the grill that didn’t come from the little market in Coffman Cove and cost more than a tank full of California gasoline.

I honestly figured we’d broken the seal and that we hadn’t, after all, mistimed the run. I was expecting the fish to start coming to hand at a regular clip. But it wasn’t to be. Mark and our other fishing buddy, Sam, didn’t build on the momentum. The fish, apparently, was just a one-off.

More Like This

I walked down the creek another quarter-mile or so and crossed a hip-deep channel. I wanted to be closer to the salt where I suspected there were fish staging for a run up the stream, but then, I’d been suspecting such a run for days, with no such run happening. At the lip of a run where two braided channels reunited over the gravel, I cast a bright pink Slumpbuster across the creek, mended once and let the neon fly swing into the current.

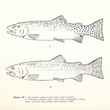

Silvers are the most underappreciated fly rod fish in the salmonid family. Say what you will about your Bristol Bay rainbows or the giant browns of Tierra del Fuego. When a fresh coho hits a fly, you’ve succeeded in pissing it off. And you can feel its anger pump up the leader and the fly line, into the backbone of your fly rod, which should, at the very least, be a stiff 7-weight. An 8 will serve you better.

And then it’s gone, rushing back to the salt like a Metro commuter trying to get on the orange line before the door closes. It takes your line. It tests your backing knot. Most of all, it tests your mettle. As I stood at the lip of the run watching my backing spin off the spool in a bright orange blur, I had to figure out how I was going to get the upper hand in this fight. The only answer I could come up with was the most elementary.

You gotta go after it, dummy.

So I plunged into the creek, crossed a waist-deep side channel and began lumbering down the salty slick bank toward the ocean where this fish clearly wanted to be.

We’d spent the first few days “trout fishing” for Dolly Varden and occasionally, just to feel the tug, swinging Egg-sucking Leeches for pink salmon that were staging by the thousands in every pinch-point and deep pool in nearly every creek we fished. Now and then, we’d catch a footlong rainbow (I hopefully noted that these fish were probably down-running steelhead smolts), and if we fished streams closer to their terminus in the salt, we’d hook a decent sea-run cutthroat now and then, too.

But the silvers were a no-show. They just … weren’t there. Maybe they were early. Maybe late. Nobody really knew. We just knew that, in appreciable numbers, the highlight of the summer salmon season was largely a bust.

Until that day. Until Mark popped the cork on that first fish. And then … I broke the bottle.

As I sprinted down the creek, I let out an appreciable string of loud and profane language so my buddies knew that I was hooked up. It was days in the making, this encounter with this fish. We’d slogged through the rainforest, ducked under fallen cedars while cold creekwater topped our waders and drained into our nether regions. We put up with rain that could only be described as … unrelenting. We’d navigated copses of impossibly thorny devil’s club, fallen into hidden holes in the mossy rainforest floor and put more miles on a sketchy old, rented Yukon than it should have been able to handle.

We’d taken to becoming full-on foragers — the chanterelle and chicken-of-the-woods hunting was fruitful, but it didn’t fill our bellies with fresh-from-the-salt silvers. It didn’t scratch the itch we’d all come here to scratch.

So, yeah, it felt pretty good to run and reel at the same time as I pursued the belligerent fish, hoping against hope that I’d be able to turn the fish before it reverted to full-on “ocean mode” and and escaped altogether, quite possibly with a 100 feet of fly line and 200 yards of 20-pound backing.

It took me a while. A long while, honestly. I’d reel and retrieve line only to have the 8-pound fish catch its breath and go on another hot-fish run. So, yeah, when I finally beached the behemoth on the bank, I looked at that limb through a fairly unique lens, at least for me. I rarely keep fish. Even salmon. But I didn’t feel the least-bit guilty for ending that fish’s life. Filleted on the grill that evening, as the three of us tipped back glasses of fairly decent whiskey over ice, it looked pretty damned good. Tasted good, too.

And no, the run never showed, at least not in earnest. Sam got into a couple of silvers a day or two later, but the fish seemed to be trickling in. We never did fill 25-pound fish boxes with frozen coho, but we did, thanks to a creative bargain struck up with a summer resident of Coffman Cove at the town’s only bar one night, manage to leave Alaska with some hard-frozen halibut. Our mushroom hunting prowess paid off with a righteous trade.

We did catch enough to keep from diving into the freezer in Coffman Cove for pork chops or steaks. And we scratched the itch. Sort of.

Comments